Excerpt - chapters 1 & 2

History of Metropolitan Planning Organizations

Monograph from a series of articles - January 1998

By Mark Solof

The United States may be one nation under God but, politically, it is

fractured into a multitude of jurisdictions — states, counties,

municipalities, school districts, election wards and more. While

necessary for governance, taxation and administration of public

services, these jurisdictions, for the most part, bear little relation

to the distribution of population and economic activity across the

landscape.

Over the last century, the settlement of land in

ever-widening rings around the nation's major cities has created

regional economies that span local government boundaries and often

state lines. In effect, the invisible hand of the market has shaped

the man-made landscape with little regard to the formal divisions

decreed by government.

The federal government has

recognized this organic, market-driven growth process by identifying

over 300 "metropolitan areas" across the country. According

to the U.S. Census Bureau, each consists of "a core area

containing a large population nucleus, together with adjacent

communities having a high degree of economic and social integration

with that core."

The federal government has also

recognized that the integrity and vitality of these areas are

dependent on the large-scale circulation of goods and people over

regionwide transportation networks. Yet the fragmented political

authority in most metropolitan areas makes it difficult to address

regional transportation impacts and needs.

For over two

decades, the federal government has sought to address this failing by

requiring states to establish Metropolitan Planning Organizations

(MPOs), composed of local elected officials and state agency

representatives, to review and approve transportation investments in

metropolitan areas.The North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority

is the MPO for northern New Jersey.

But because they bridge

traditional boundaries and lines of authority, from the start, MPOs

have been controversial. Critics have argued that they usurp

legitimate functions of state governments and constitute an

unnecessary layer of bureaucracy. Supporters say they are important

mechanisms for insuring local control over federal funding and that

they deserve wider authority to implement the plans they create.

Congress,

while consistently upholding the need for MPOs, periodically has

refined their functions and authority. During the fall of 1997, it was

in the midst of doing so again as it considered reauthorizing the

Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act, the enabling

legislation for MPOs .

To provide historical perspective on

this Congressional debate, the NJTPA published a series of three

articles on the history of MPOs which appeared in the NJTPA Quarterly

during 1996 and 1997. The articles made use of secondary sources to

sketch the origins and administrative history of MPOs in the context

of the broader developments in the nation, government and the field of

regional planning. This publication provides the full text of the

history series with added source notes and a bibliography.

Chapter 1 - Origins of Regional Planning: 1900-1940

Growth of the nation's metropolitan areas was made

possible and sustained by improvements in the transportation system.

In the 19th century, canals and then railroads helped knit together

local and regional markets into a single national economy. Cities with

long-established marine ports such as New York and those situated at

the hub of major rail routes such as Chicago became the command

centers for the emerging national economy. Their industries took in

raw materials and fed back finished goods to the rest of the nation.

They also served as the headquarters of new business organizations,

nationwide in scope, which generated growing numbers of well paying

jobs, swelling the ranks of the middle class.

As the cities

prospered, they drew in waves of immigrants from around the globe.

Soon, new innovations in transportation — horse-drawn railways,

electric streetcars and finally, the automobile — provided the

circulation systems needed for further growth, spreading population

and productive capacities into wide regions around the urban core.

Each city came to sit "like a spider in the midst of its

transportation web," according to Lewis Mumford.

Imposing

order on the rapid and often chaotic growth of metropolitan areas

initially became the cause of Progressive Era reformers, academics and

specialists in the new field of city planning. While their most

visionary plans were never realized, they conducted important studies

of regional needs and laid the groundwork for eventual federal

programs to support comprehensive regional planning. This chapter

traces the origins of regional planning in the first decades of the

century.

Progressive Roots

Recognition of the need for planning on a regional scale

has its roots in the "Progressive Era," roughly

the

first two decades of the century. This was a time of great optimism

for the growing middle class, when science was seen as offering the

path to a more prosperous, efficient and orderly future. Applying

scientific principles, industry helped satisfy material wants through

mass production of goods and helped ease domestic burdens with a

succession of new electric appliances.

Meanwhile, a new

intellectual elite of "social" scientists promoted the

reorganization of public and private institutions along more rational

lines. In consort with business leaders and reform-minded politicians,

this elite initiated a variety of crusades to improve the lot of the

mass of people, economically and socially. They advocated government

run by civil servants, breakup of monopoly companies, "home

economics," compulsory education beyond grade school and

prohibition of alcohol.

One of the great challenges faced

in the Progressive Era was massive urbanization. Cities were growing

rapidly as a result of both unprecedented immigration as well as the

influx of population from rural areas. Social reformers, taking aim at

overcrowded and unhealthful living conditions, pressured city

governments to institute sanitation and building codes. Later they

fought haphazard development patterns, including the siting of

commercial and industrial facilities in residential neighborhoods. In

response, cities drew up plans for segregating land uses and

instituted the first zoning ordinances to enforce them.

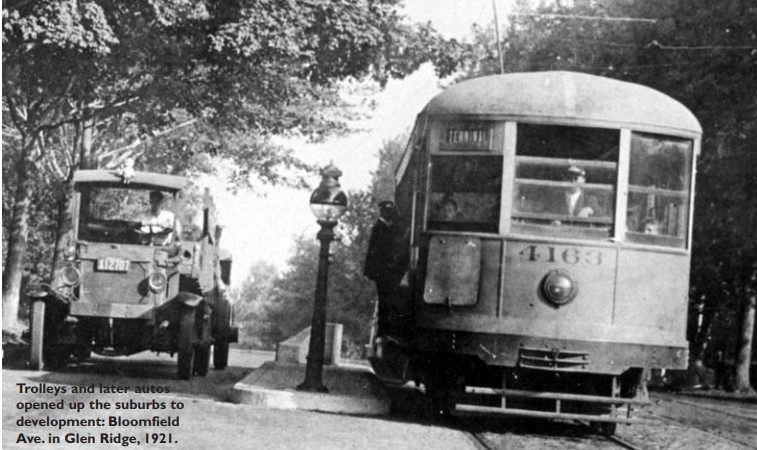

Cities

were also expanding outwardly. Many families fled inner-city crowding

to homes in suburbs that had access to city jobs via streetcar or

commuter rail lines. By the 1920s, as automobile ownership grew, wider

areas were opened up to settlement, with many rural villages

transformed by a wave of housing development for urban commuters. Most

of this growth occurred with little forethought or government

intervention. Indeed, existing government structures could only

address the trends on a piecemeal basis and, as a result, many

problems were left unaddressed including mounting highway congestion,

polluted rivers, disappearing open spaces and inadequate water and

sewer systems. It was only natural that the

Progressive Era

emphasis on promoting rational organization would be brought to bear

on the growing dispersion of population and economic activity in broad

regions around major cities.

Practical Needs

The first efforts at regionwide planning began in the

1920s. While academics provided the theory and social science tools

for regional planning (see sidebar p. 8), practical considerations

motivated their use. For instance, by the end of World War I, a

long-running dispute between New York and New Jersey over rail freight

business reached a point where only a solution at a regional scale was

possible. The dispute centered on rates charged by rail companies that

encouraged goods to be moved from rail terminals in New Jersey to

ships berthed in New York. New Jersey claimed the rates limited the

development of maritime business on its side of the port. At one

point, a lawsuit threatened, Solomon-like, to split the port into two

zones, reducing its ability to efficiently serve shippers and leading

to the loss of business to other East Coast ports.

New York

business leaders recognized the threat and proposed a new bi-state

agency to provide unified planning and policies for the port. Backed

by the federal Interstate Commerce Commission, the business leaders

finally succeeded in 1921 in getting the two states to create the Port

of New York Authority (later to become the Port Authority of New York

and New Jersey). The authority was the first interstate governmental

body in the nation and the first special-purpose "authority"

with power to issue bonds and make investments while insulated from

political control. In its first year, the Port of New York Authority

set about developing a comprehensive plan for improving the entire

port with new terminals and connections among rail lines

As

this ambitious port plan took shape, other planning efforts were

initiated to address a host of emerging regional-level problems.

Again, New York area business leaders, together with a growing number

of professional city planners, broke important ground. In the early

1920s, the Russell Sage Foundation appointed a committee to develop a

"Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs." The work grew

into a massive undertaking, including extensive surveys, data

collection and economic projections, focusing upon New York City and

500 communities in three states within commuting distance of

Manhattan. The pioneering work would continue for most of the decade

during which most other major cities in the U.S. initiated similar

"comprehensive" regional plans.

The first volume

of the New York plan was issued in 1929 and presented recommendations

on nearly every aspect of regional development, including calls for

the development of satellite cities in outlying areas, the control of

land-use to preserve open spaces and the construction of new rail and

highway networks.

Implementation of such a far reaching

plan was problematic. The authors hoped that the logic of their

recommendations would do much to promote voluntary compliance by

affected governments in the tri-state region. A private planning

organization, the Regional Plan Association, was created to promote

this compliance and conduct follow-up research.

However,

the experience of the Port of New York Authority did not bode well for

achieving voluntary compliance. Lacking power to force cooperation

among the highly competitive freight rail companies in the region, the

Port Authority was blocked in implementing many elements of its plan

for creating an integrated freight rail network.

Critics

argued that the recommendations of the Regional Plan of New York, and

of comprehensive plans elsewhere in the country, would be similarly

blocked by the competing interests of local governments. One planning

professor, Thomas Reed, in 1925 contended that the only way to insure

effective regional planning was the creation of "areawide"

governments with power over municipalities in setting policies for

regional infrastructure.

The Great Depression

Questions about the implementation of comprehensive plans

in New York and other cities became all but moot in the face of the

economic collapse of the Great Depression. Where toll or other

dedicated funding sources were available or where the federal

government would foot the bill, selected infrastructure projects

recommended by regional plans were built. The New York region fared

particularly well, with the George Washington Bridge, Lincoln Tunnel

and other major transportation facilities built in the 1930s.

But,

by-and-large, visions of promoting orderly urban regions with planned

communities and efficient infrastructure systems, were abandoned as

cities struggled with desperate social and economic conditions.

Still,

the regional planning experience of the 1920s exerted an important

continuing influence. Through the empirical techniques of the social

sciences, planning efforts in major cities had documented the regional

nature of many social and economic problems. In doing so, they also

created a strong case for new institutions and decision-making

mechanisms such as authorities and regional planning commissions to

supplement fragmented political structures.

The federal

government, for its part, carried the torch of regional planning

forward as it intervened to revive the economy in the 1930s. President

Roosevelt, with great interest in natural conservation, encouraged and

supported cooperative planning by governments in river valleys to

address flood control, soil erosion and other shared needs. He also

initiated a massive federal experiment in regional planning by

creating the Tennessee Valley Authority which addressed not only water

resources issues but electrification, agricultural improvement,

housing and economic development.

Many New Deal programs

were administered regionally and encouraged cooperation among local

officials. The Public Works Administration, in particular, helped

state and local governments develop the planning capabilities needed

for large-scale infrastructure projects. But there was a catch.

Planning was to be in accordance with national standards as a

condition for the receipt of federal infrastructure aid. This

requirement set the pattern for future intergovermental relations: the

federal government used aid as a lever for promoting achievement of

national goals and for persuading state and local governments to look

beyond their narrow self-interests in making infrastructure and social

investments.

Chapter 2 - Regional Responses to the Suburban Land Rush:

1940-1969

At the end of World War II, America was transformed by

rapid suburbanization which brought housing, retail and other

development sprawling out in every direction around major urban

centers. As the transformation proceeded, public and private leaders

recognized that existing government structures were inadequate to deal

with the problems that arose — not the least of them, inadequate

transportation, water and other infrastructure systems, the loss of

open spaces and the decline of urban neighborhoods.

This

recognition prompted the creation of numerous regional planning

bodies. With regulatory and financial backing by the federal

government, these bodies by the 1960s took on a variety of official

planning functions for their regions. Still, they were seldom able to

exert influence over the land use decisions of local governments or

the transportation decisions of state agencies which helped drive the

continuing suburban land rush.

This chapter traces the

post-war developments in regional planning that set the stage for the

formal establishment of MPOs in the early 1970s.

Preparing a New Future

During World War II, government and industry leaders were

keenly aware of the need to plan for the post-war period. After a

decade or more of pent-up demand for housing and consumer goods, the

nation was poised for an unprecedented peacetime economic boom.

However, the leaders knew that if this demand was not capitalized upon

effectively, the nation could easily slip back into the unemployment

and stagnation of the pre-war years.

Thus, alongside the

patriotic fervor for the war effort, planning for a new post-war

America became a national preoccupation. In a number of major cities

regional alliances were launched in which public officials joined

forces with private industry and surrounding local governments to

chart strategies for their post-war future. Their efforts were

supported at the federal level by the National Resources Planning

Board (NRPB), until it was disbanded by Congress in 1943. The agency

urged a "comprehensive" approach to post-war planning that

would make use of surveys and community forums and recognize "the

interrelatedness of problems of population, economic activities,

social patterns [and] physical arrangements."

But by

and large the alliances paid little heed to urgings of NRPB for

comprehensive planning-or even to the lessons learned in the 1920s

about the problems of unfettered regional growth. The dominant view

was that, if regions were to seize the coming economic opportunities,

bold initiatives would be required. Rather than engage in the cautious

planning advocated by the NRPB, most regional alliances focused upon

preparing housing, business development and infrastructure projects

that could be quickly implemented with the war's end.

Planning

new freeways became a favored activity. Many of the regional

transportation systems envisioned were straight out of the General

Motors' "Futurama" exhibit at the 1939 World's

Fair — cities linked and served by networks of congestion-free,

limited-access highways that presumably would make the nation's

crowded and run-down mass transit systems a thing of the past. In

1944, Congress gave its endorsement to this "motor age"

vision with initial authorization for construction of a nationwide

interstate highway system. If the nation was to move boldly into the

future, apparently it would do so solely by automobile.

Suburban Land Rush

By the end of 1946, 10 million men and women were

discharged from the armed services and new family formation rose to a

record 1.4 million per year. The need for new housing to accommodate

them reached near-crisis proportions. The national housing agency

estimated that five million new housing units were needed immediately

and 12.5 million would be needed over the next decade.

Private

developers jumped at the opportunity. Using pre-fabricated materials,

cookie-cutter plans and standardized construction techniques to create

"tract" housing developments, the developers sought to

attract veterans — with their generous GI mortgage benefits — and

middle class urban dwellers eager to enjoy the privacy and amenities

of new, detached suburban homes.

The most aggressive and

successful of the private developers was Levitt and Sons, who

transformed potato farms on Long Island into the 17,000-home

Levittown, creating the model for similar communities in Pennsylvania

and New Jersey. By 1950, according to one estimate, Levitt was

producing one four-room house every 16 minutes.

But blacks

and other minorities were generally not welcomed. Even after 1948 when

the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that clauses in sales agreements

discriminating against minorities were unenforceable, many contracts

still contained them and realtors and developers used

"steering" and other methods to keep non-whites out of prime

suburban locations.

Still, in all, three-fifths of all new

housing in the late 1940's was built in the suburbs. On the heels

of the suburban housing boom, retailers, manufacturers and other

businesses sought out suburban locations, resulting in an increas- ing

dispersion of economic activity that had long been compacted in and

around major cities.

The dispersion, in addition to meeting

the material and employment needs of the new suburbanites, was viewed

by military officials as having strategic benefits, making the

nation's population and productive capacities less vulnerable to

nuclear attacks against major cities. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright put

it bluntly: "The urbanite must either be willing to get out of

the city or be resigned to blowing up with it." This cold-war

calculus provided further impetus to national-level support for a

continuing suburban land rush.

Federal Planning Aid

Inevitably, many rural communities faced growing pains in

accommodating waves of new residents. In some areas, the pains became

outright sickness. Symptoms included poorly laid-out housing

developments and inadequate schools, roads and water and sewer

systems. Many homeowners also faced their share of woes from slapdash

building methods, including leaky roofs and faulty sewer hookups.

Planner and historian Lewis Mumford, surveying the growing chaos in

many areas, termed it "the suburban fallout from the metropolitan

explosion."

The nation's cities, too, were

shaken. The loss of middle class residents and business further

exacerbated the social and economic problems that had received scant

attention through the long years of economic depression and then

war.

Congress responded with major housing legislation,

first in 1949 and again in 1954. The acts primarily supported

continued suburban development, with financing and insurance programs

benefiting both homebuyers and builders. But the acts also authorized

federal aid to cities for urban renewal and public housing and

supported new regional planning efforts. Section 701 of the 1954 Act

for the first time gave federal grants for councils of governments and

other metropolitan planning agencies to promote cooperation in

analyzing and addressing regional problems.

Testifying

before Congress, urban planning professor Robert Mitchell argued that

such planning aid was needed to build "awareness that central

cities and suburbs are interdependent and cannot survive in the

present governmental and physical chaos."

The federal

aid proved popular, prompting the formation of nearly 100 metropolitan

planning bodies. Yet, while the new agencies improved

intergovernmental cooperation, they generally were hamstrung by their

inability to directly shape local government land use policies.

Indeed, many local officials supported regional planning only to the

extent that it would sustain their capacity to accommodate the

windfall of development projects coming their way.

Some

communities chose to go it alone, hiring consultants to develop master

plans that would rein in the more disorderly aspects of growth. The

extreme case was the community of Mountain Lakes, New Jersey, which

purchased all the town's vacant, developable land to be parceled

out only for those projects that fit the sensibilities of its wealthy

residents.

Interstate Highways

The ambivalence on the part of local officials towards

regional planning changed dramatically with the 1956 Federal Aid

Highway Act. The legislation authorized construction of the

multi-billion dollar, 41,000 mile interstate highway system as well as

providing aid for primary, secondary and lesser roads. The system

constituted the largest construction program in the nation's

history, on the scale of 60 Panama Canals. With the choice of routes

left up to state highway departments, many local officials found new

cause to embrace cooperation through metropolitan planning agencies to

avoid having routes imposed on them and to gain bargaining clout in

negotiations with their states.

Still, the resulting

cooperation had few of the features of the comprehensive regional

planning advocated years earlier by the NRPB when the interstate

system was conceived. Rather much of the "planning" was of a

narrow, technical nature focusing on routing alignments. Despite the

urging of the planning community, the Act did not require routes to

conform to metropolitan plans already in place or to give

consideration to crucial land use issues, such as how particular

routes could open up wide areas to new waves of suburban development

and sprawl. Also the Act all but neglected the further damage that

could be done to urban transit systems, which already were pitched

into a steep decline due to competition with the automobile.

The

decision to forge ahead with the massive interstate highway system

with only dim recognition of its potential consequences partly stemmed

from the influence on Congress of those with something to gain from

the system — the defense establishment, developers, auto manufactures,

oil companies, state and local engineers and others.

But it

also reflected a peculiarly-1950s outlook about the future. It was a

decade of national self-assurance when American industrial and

military might dominated much of the world. Any challenges which might

appear on the horizon, the view went, would yield to technology and

American ingenuity.

Faith in the future was also strong

among transportation officials in the 1950s. Even the demise of mass

transit systems was seen as amenable to technical fixes. For instance,

a 1956 Brookings Institution report stated that "In the coming

decade the development of regional mass transportation by helicopter

or convertiplane may provide the longer distance commuting services

now provided by interurban buses and commuter rail lines."

All

this added up to a confidence in building large-scale projects in the

name of progress, leaving the consequences to be sorted out later. It

was an outlook personified in "master builder" Robert Moses

who, from the 1930s on, oversaw the construction of major highways,

bridges and parkways in and around New York City — as he lashed out at

"ivory tower planners" for being preoccupied with potential

complications.

Three-C Planning

By the late 1950s, the effects of a decade or more of

rapid suburban growth began to dampen the widespread "build it

now" enthusiasm. Many planners and public officials were alarmed

at the nation's changing landscape. In 1958, planner William

Whyte noted that a traveler flying from Los Angeles to San Bernardino

"can see a legion of bulldozers gnawing into the last remaining

tract of green between the two cities." On a flight over northern

New Jersey, he said, the traveler "has a fleeting illusion of

green space, but most of it has already been bought up and outlying

supermarkets and drive-in theaters are omens of what is to

come."

These concerns led to studies during the

Eisenhower Administration of new government structures and policies

that could help improve local planning and coordination. Many study

recommendations were enacted under the Kennedy Administration as part

of the Housing Act of 1961 which provided grants for mass transit and

open space preservation and expanded funding and incentives for

metropolitan transportation planning.

A further, and

historic, step in addressing the problems of rapid suburbanization

came with the enactment of the Highway Act of 1962. It made federal

highway aid to areas with populations over 50,000 contingent on the

"establishment of a continuing and comprehensive transportation

planning process carried out cooperatively by state and local

communities." This required planning process, known as

"three-C" planning for its continuing, comprehensive and

cooperative features established the basis for metropolitan

transportation planning used to the present day.

While

regional cooperation and comprehensiveness had been long-sought goals

of the planning community, the Act's requirement for continuous

planning recognized that in a rapidly changing and increasingly

complicated environment, which included dramatic population growth

resulting from the post-war baby boom, regional plans had to be

dynamic documents, subject to revision based on continuing data

collection and feedback. Advancements in computer technology and

social science research techniques became important tools for

conducting this continuous planning.

Three-C in Practice

In the year following the adoption of the 1962 Act,

governments throughout the country scrambled to put in place the

required three-C process. The response of officials in the New

York-New Jersey-Connecticut metropolitan region was typical of major

urban regions. Since the late 1950's, the non-profit Regional

Plan Association, with input from many of the area's officials,

had been developing a comprehensive plan for meeting the region's

infrastructure needs. As a result of the 1962 Act, a new official

body, the Tri-State Regional Planning Committee (later the Tri-State

Regional Planning Commission), was created to build upon this planning

effort and administer the region's three-C transportation

planning process. A number of similar metropolitan planning bodies

were created across the country and some existing voluntary and

quasi-official regional bodies gained official status.

Despite

the high initial expectations created among many planners by the new

organizations and the enlightened nature of the three-C requirements,

the weaknesses of the Act became clear in subsequent years.

Implementation of the Act was the responsibility of the federal Bureau

of Public Roads (BPR) which was closely allied with state highway

departments and organizations dedicated to roadway construction.

According to urban planning professor Thomas A. Morehouse, the three-C

planning requirement was seen by these highway interests as "a

potentially disruptive innovative force, threatening established

policies, procedures, commitments and systems of

decision-making." Of particular concern to highway interests was

the possibility that local officials acting through new regional

organizations — with mandates for comprehensive planning in hand —

could block or slow construction of segments of the interstate system

which were then were being pushed through densely populated

metropolitan areas.

To avert the threat, BPR interpreted

the Act in ways that preserved the authority of state highway

departments. For instance, states were able to fulfill the

"cooperative planning" requirement by negotiating agreements

directly with local governments, bypassing though it was now tempered

by somewhat greater local participation and informed by increasingly

sophisticated technical studies. These agreements typically allowed

local officials to participate in technical studies, initiated and

dominated by state highway departments, for planning the

implementation of specific roadway projects or for establishing

long-range regionwide capital plans. Land use, mass transit and social

issues were usually given only passing consideration.

One

result of BPR's "artful" interpretation of the required

three-C process was that regional planning agencies were left largely

as adjuncts to state highway departments which relied upon them for

collecting and interpreting data and perhaps for input on how road

construction within their regions should proceed. In effect, the 1950s

"build it now" approach to project development lived on in

the 1960s, though it was now tempered by somewhat greater local

participation and informed by increasingly sophisticated technical

studies.

1960s Progress

While many of the hopes of the early 1960s were never

fully realized, the cause of improved regional planning was by no

means vanquished. With crucial support by President Johnson and his

political allies, major transportation and housing legislation during

the decade progressively expanded the role and authority of regional

planning agencies (see box, right). In his message to Congress shortly

after his election, Johnson noted that in confronting housing,

transportation or other urban problems, metropolitan planning was

needed to "teach us to think on a scale as large as the problem

itself and act to prepare for the future as well as repair the

past."

In addition to new responsibilities in the

areas of environmental and transit planning, regional bodies were

entrusted with reviewing all applications for federal aid to insure

they were consistent with areawide plans and were coordinated with

other federal-aid projects.

Though carefully crafted to

preserve the prerogatives of business and avoid the taint of "big

government," these legislative requirements were a significant

step towards comprehensive regional planning. Their enactment

reflected an often grudging recognition among politicians that the

nation could simply not afford to build major projects that would

transform its landscape and communities without attention to the

consequences that, more often than not, played out on a regional

scale. This recognition sprang, on the one hand, from increasing

sophistication in social and environmental sciences that brought to

light the damage done by unthinking policies of the past and that

offered important new tools and methodologies for planning the future.

On the other hand, mass movements and urban riots showed that narrow,

technical approaches to problems could neglect critical social

factors, with potentially devastating results.

The greatest

impact of the legislative mandates was felt in the nation's

largest metropolitan areas where regional agencies like the Tri-State

Regional Planning Commission in New York and the Delaware Valley

Regional Planning Commission in Philadelphia took on multiple official

functions in cooperation with states and local governments. However,

across the country, the bulk of staff resources, engineering expertise

and political influence needed to see plans through to implementation

continued to reside in state bureaucracies.

Particularly in

many smaller urban areas, regional agencies found themselves going

through the motions in fulfilling federal requirements while key

decisions on transportation and other policies were made in state

capitals.

Chapter 3 Toward More Balanced Transportation Through MPOs:

1969-1983

For much of the 1950s and 1960s, America built highways

on a grand scale. With billions of dollars from federal gasoline

taxes, each year 2,000 miles or more of elaborately-engineered

interstate highways were dynamited through mountains, lifted over

rivers, snaked across the countryside and bulldozed through

denselypopulated urban areas. The highway building effort commanded

wide public support and was backed by a powerful coalition of

politicians, business leaders and interest groups.

Yet by

the early 1970s the highway juggernaut was in serious trouble. Facing

often fierce opposition in urban neighborhoods, concerns about the

environment, funding shortfalls and other complications, highway

projects were slowed, scaled-back and even blocked in many locations.

Congressional hearing rooms became the scene of heated debate over

efforts to broaden federal policy to embrace other transportation

goals-such as supporting mass transit systems and ridesharing

programs-that would reduce the nation's dependence on automobiles

for mobility.

To help the nation cope with the vastly more

complex transportation policy environment in the 1970s, Congress

required each urbanized area to establish a Metropolitan Planning

Organization (MPO) composed largely of local officials. Congress hoped

MPOs would help build regional agreement on transportation investments

that would better balance highway, mass transit and other needs and

lead to more cost-effective solutions to transportation problems.

As

this chapter recounts, MPOs generally failed to live up to

expectations during their first decade. Eventually, they faced

cutbacks in funding and support for their missions, though formal

federal requirements for transportation planning through MPOs

continued...